Fante Confederacy: Middlemen in the Coastal Slave Trade

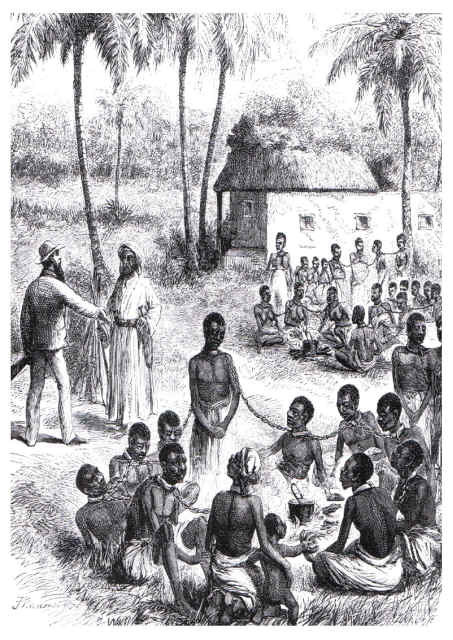

While the Ashanti operated from the interior, the Fante peoples controlled many coastal port towns that became key hubs in the slave trade. By the 1700s, European powers — notably the British — had established forts and trading posts along the coast, relying heavily on Fante middlemen to procure enslaved people from the interior.

The Fante, though militarily weaker than the Ashanti, used their strategic location and political alliances (especially with the British) to their advantage. Slave trading brought wealth, infrastructure, and influence to Fante elites. Coastal towns flourished economically, even as the human cost remained catastrophic.

Some notorious local slave dealers were Fante or coastal elites such as Oheneba John Corrantee (Korankye), Richard Brew, the Hayfords, and the Bartels — names that do not trace to Ashanti heritage.

In popular memory, these individuals are controversial figures. For example, in Jamaica, the name John Correntee became "John Crow" — now the local term for a vulture and a traitor, symbolizing betrayal by African slave sellers.

Ashanti–Fante Conflicts and Coastal Power Struggles

Ashanti expansion often brought them into conflict with the Fante, especially over access to European traders and coastal forts. Between 1720 and 1750, the Ashanti waged wars of conquest, including defeating the Akyem in 1742, which opened routes to the coast.

In 1806, the Ashanti pursued two rebel leaders into Fante territory, sparking conflict when the British refused to surrender the fugitives. One of them was later surrendered by the British and the other escaped. The following year, the Ashanti–Fante War (1807) broke out, with the Ashanti emerging victorious.

Further wars followed, including the Ga–Fante War (1811) and the Ashanti–Akim–Akwapim War (1814). Each conflict not only expanded Ashanti territory but also strengthened their direct access to Atlantic trade routes, reinforcing their role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

By 1816, the Fante Confederacy was absorbed into the expanding Ashanti Empire.

Slave Trade and Firearms: A Cycle of Violence

The Ashanti used the profits from slave trading to purchase European firearms, which were then used to wage further wars, capture more people, and sell more slaves — a brutal cycle of violence.

This strategy brought short-term gains in terms of wealth and territorial expansion. But over time, the constant warfare weakened the empire. As the British increased their colonial ambitions in the 19th century, the once-mighty Ashanti found themselves increasingly vulnerable.

Decline and Abolition

By the early 1800s, Britain began to curtail its role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The Slave Trade Act of 1807 outlawed the trade for British subjects — which included their Fante allies on the coast. Although illegal slave trading continued for decades, the act marked a turning point.

In 1874, when the Gold Coast officially became a British Crown Colony, the abolition of slavery itself was pursued. * By 1875, it was declared that all children born to enslaved people would be free, initiating a gradual process of emancipation. (* see below article)

The Broader West African Context

While the Ashanti and Fante were central players in Ghana’s slave trade, they were not alone. Every major kingdom — from the Denkyira in the south to the Bissa and Mamprusi in the north — had participated.

The Denkyira, for example, were prominent slave traders long before the Ashanti Empire rose to power, especially during the reign of Boa Amponsem. They sold even members of Akan clans that would later unite to form the Ashanti state.

In the northeast, the Bissas captured and sold Kusasi people from what is now Burkina Faso until the Mamprusis intervened.

A Shared Legacy

The uncomfortable truth is that no ethnic group in present-day Ghana is completely innocent when it comes to the slave trade. Whether through direct raids, warfare, or coastal trading, many groups participated in and profited from this system of exploitation.

Even after the Ashanti later suffered enslavement themselves — with many ending up in places like Jamaica — the legacy of their earlier involvement remains part of their complex history. Ironically, figures like Amy Ashwood-Garvey, the first wife of Marcus Garvey, traced her ancestry to Dwabeng, an Ashanti town.

Reconciling With History

The involvement of the Ashanti and Fante in the trans-Atlantic slave trade reflects the tragic complexities of African agency during the era of European colonial expansion. These kingdoms were not passive victims but active participants — some driven by economic survival, others by ambition, and all influenced by the pressures and opportunities of a global trade network built on human suffering.

Today, as modern Ghana seeks to reckon with its past and honor the memory of those who were taken, it's vital to face the full story — including the role played by local powers. Acknowledging this complex legacy is not about placing blame, but about telling the whole truth and ensuring that history is never repeated.

Note

As a further indication of British colonial policies, in 1902, legislation was enacted that made it illegal to "compel or attempt to compel the services" of another person, which signaled a step towards regulating labor practices in the colony. However, it is important to note that slavery as an institution was not explicitly abolished at this time. This hesitance stemmed from British officials’ concerns that a complete abolition of slavery might lead to "internal disorganization" within the region, as they feared such a drastic change could disrupt the existing social order.

While the British authorities formally prohibited chattel slavery in 1908, the enforcement of this law was not initiated until the 1920s. This delay highlighted the complexities and challenges of transitioning from an entrenched system of slavery to one that recognized individual freedoms, reflecting the broader tensions that characterized colonial rule and the evolution of social policies in British West Africa.

Article by (c) Remo Kurka 2025